With an eye on expanding its economic prowess, which could in turn fuel its global agenda, China has been investing billions of dollars on infrastructure development around the world.

The latest pledge of $124 billion was announced at the ‘Belt and Road’ Summit in Beijing in May. Focusing on trade, telecommunication and infrastructure connectivity and cooperation, the plan is oriented to reviving the ancient Silk Road project linking China to Persia and the Arab world.

The 2013 initiative (also known as One Belt One Road or OBOR) involves the land-based ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and the sea-based ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’. Together, the routes cover more than 60 countries across Asia and Europe via Southeast Asia, South Asia, Central Asia, West Asia and the Middle East.

Given the scale of the plan (at least $2 trillion) and its expansive reach, the plan offers interesting opportunities for the countries in the Middle East.

To fund this ambitious project, China instituted the New Silk Road Fund with $40 billion and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) contributing $100 billion.

The AIIB board includes representatives from Saudi Arabia and Iran. Further, the AIIB provided $300 million finance in 2016 to expand Oman’s Duqm Port and to kick-start the Sultanate’s first railway system.

These developments must be seen in the context of Beijing unveiling its first ‘Arab Policy Paper’ in 2016, which set out the country’s development strategies with Arab countries to ensure a win-win situation.

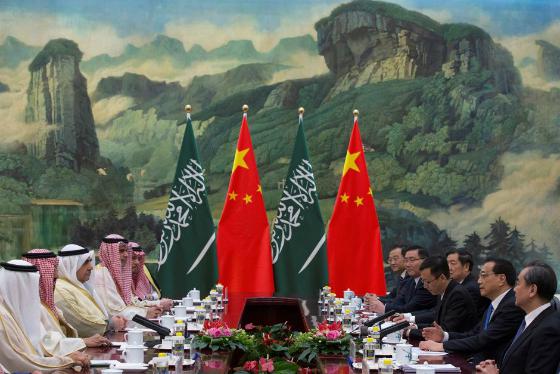

Soon after, President Xi Jinping toured the Middle East. By visiting Saudi Arabia, Iran and Egypt, especially during the height of the Riyadh–Tehran feud, Beijing demonstrated that the region is part its strategic focus.

This led many to wonder if these moves indicated a ‘Chinese pivot’ to the region.

Motivating the newfound interest in the region is the fact that China’s trade with the Middle East surged by a whopping 600 per cent during the 2004-2014 period.

In 2015, China surpassed the United States as the world’s top importer of crude oil. More than half the 6.2 million barrels per day of crude that China imports is extracted in the Middle East.

As a way of enhancing this synergy, the Arab Policy Paper stated that China and Arab countries will adopt a three-pronged strategy – one, energy cooperation as the core infrastructure; two, construction and trade and investment facilitation; and three, innovative technologies in nuclear energy, space satellite and renewable energy.

As a result, although not directly along the Belt and Road routes, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries could harvest high stakes in the project.

The GCC countries possess high quality infrastructure, especially seaports and airports, which could serve as facilitators for the initiative. The GCC countries could also benefit from joint investment in infrastructure projects in some of the countries that are part of the initiative.

Saudi Arabia has welcomed China’s attempt to revive the ambitious ancient trade routes since it complements the Kingdom’s equally ambitious Vision 2030.

Given that a substantial part of China-UAE trade is re-exported to Africa and Europe, which are the core destinations of the initiative, the UAE could serve as a hub for Chinese companies.

For a start, DP World facilitated the first direct freight train from Britain to China in April. The journey that revives the Silk Road is reportedly cheaper than air cargo and faster than sea cargo, which increases its potential.

DP World reportedly operates 20 terminals across China, Southeast Asia and South Asia, which makes it an important player in the Belt and Road initiative.

According to the chief of the Dubai-headquartered ports company, Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem: “We will work with the Chinese to prepare our ports.”

Since there are a number of hotspots along the Belt and Road routes in the Middle East, Chinese-GCC cooperation in the counterterrorism and security arenas acquires prominence.

The key, however, is how the GCC countries come to terms with the Chinese-Iranian partnership.

By virtue of its geographical location, Iran is a key player in China’s effort to connect Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe. In February 2016, the first direct Chinese cargo train arrived in Tehran through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan in about two weeks, compared to 45 days by sea.

Likewise, Beijing is equally enthusiastic about the “Red-Med” railway proposal that it is keen to construct across Israel, which could complement the busy Suez Canal.

Globally, the Belt and Road initiative has received mixed reviews.

On a positive note, some view it as a genuine tool to promote trade. There is also a view that “the Silk Road is not only for trade of goods…Roads transfer culture, religions and technology as well,” hence promoting peace.

On the other side, the United States, Japan, and India, among others, are worried that the Chinese project is loaded with ‘expansionist’ designs.

Countering its critics, however, Beijing clarified its stand at the recent summit of world leaders: “In advancing the Belt and Road, we will not retread the old path of games between foes. Instead we will create a new model of cooperation and mutual benefit.”

Thus, despite the challenges, the GCC and other Middle East counties could devise strategies to make China’s Belt and Road an economic, political, diplomatic and security win-win initiative.

Ameinfo

19 June