Travellers to Lebanon have long bemoaned the state of the country’s roads. Writing in the 1850s, an Irish banker, James Farley, called the route from Beirut to Damascus a “wretched mule path”. The perilous journey over rough mountain passes took four days, as long as you dodged bandits and avoided the winter snow. The mules have gone but the sorry state of the country’s roads persists. Years of political chaos, low investment and more recently the influx of 1.5m Syrian refugees, which has sapped resources, exacerbated the problem. Could a revival of railways save the day?

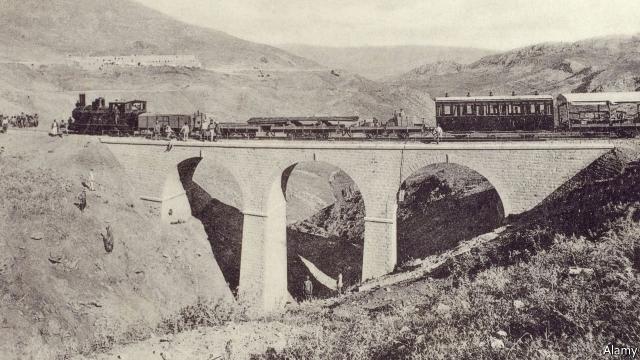

The fate of Lebanon’s rail network tracks the rise and fall of the country’s fortunes. Built by an enterprising French count when Beirut was still ruled by the Ottoman Turks, the first line opened in 1895, cutting the trip to Damascus to nine hours. Tourism, trade and a nascent wine industry set up by a French road engineer flourished. When T.E. Lawrence’s band of saboteurs blew up parts of the Turks’ Middle East rail network in the first world war, Lebanon’s dynamic railway factory produced the spares needed to mend the damage. By the eve of next world war, you could travel from Beirut to London. At its peak, the country’s railway was said to span 408km, roughly the same amount of track as today’s London underground.

The skeletal remains of Lebanon’s iron heyday are now scattered across the country. Rusting trains, dilapidated stations and tracks overgrown with wild flowers are all that is left. The civil war, which erupted in 1975 and ravaged the country for the next 15 years, gradually destroyed the network. Militias blew up the tracks. The Israeli army shelled them. Syria’s security forces dug up parts of the line to sell as scrap metal in Pakistan. An open-air nightclub in Beirut’s old central station is the closest most Lebanese will ever come to a train, provided they can afford the fancy cocktails.

Talk of restoring the tracks to their former glory is nothing new. Several government-commissioned studies since the 1990s have argued that a railway linking Lebanon’s coastal cities with Syria makes economic sense. The latest, funded by the European Investment Bank, says a line connecting Beirut to the northern port city of Tripoli would generate enough revenue to cover operating costs and recoup some of the $3bn it would take to build. A track shipping freight from Tripoli to the Syrian border and on to the city of Homs—and thus with luck farther afield in the Middle East—would cost far less and boost trade. A consortium of Italian firms is also looking at tunnelling through the mountain to reopen the Beirut-Damascus route.

Despite the enthusiasm, Lebanon’s trains will go nowhere until the war next-door stops. “No one wants to put money in when it’s still unclear what’s going to happen in Syria,” says Raya Haffar, a former finance minister. Firms from the Gulf and China are eyeing investments that seek to capture some of the $200bn needed to rebuild Syria. A railway from Lebanon’s ports to Syria’s cement-hungry cities might encourage them. But even if the war ends it will take years before work on a new rail network can begin. If Lebanon’s track record is anything to go by, its railway dreams are more likely to hit the buffers.

The Economist

05 October